One of the more peculiar, historic and almost cinematic treatments being discussed in the midst of the ebola crises is the use of blood transfusions. In movies, the blood of a survivor or someone special is often supposed to have some sort of mystical effect on the (usually villainous) recipient. It turns out, blood transfusions from people who have survived ebola are nearly as mystical.

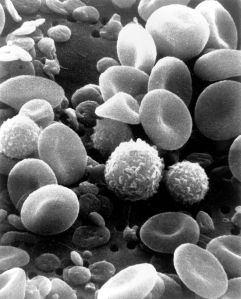

It seemed obvious to me at first that the active components in blood transfusions from ebola survivors must be anti-ebola antibodies. Such antibodies would neutralize the virus and help the immune system clear it out. And in fact, a 1999 study reported that seven patients who survived the 1995 outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo after receiving transfusions from survivors had anti-ebola antibodies circulating in their blood. One kind of antibody, called IgM, was absent in another patient who received a transfusion and died. This very small study seemed to indicate that transfusions could work against ebola and that antibodies are key to making them work. (You may be wondering why, if the transfusions worked, more patients weren’t treated this way during the 1995 outbreak. One important reason is that that blood cannot be transfused unless the donor and recipient blood types are compatible. So the treatment is limited by the number of willing survivors and their blood types.)

This idea was challenged by a 2007 study done in a nonhuman primate species, rhesus macaques. For this study, researchers drew blood from a rare few monkeys who had survived an ebola infection four or five years earlier and a second “boost” infection 30 days earlier. They transferred the blood into other, recently-infected animals, and none of them survived…even those that made a lot of antibody. There are, of course, caveats. Monkeys are not humans, after all. It is possible that they fight the virus differently. And in the discussion of the paper, the researchers admit the experiments that had successfully transferred antibody-mediated immunity in guinea pigs had not worked in rhesus macaques.

There are also caveats to the human study though. The main one being that it can’t account for the better treatment transfusion patients received compared to other patients. The seven may have survived simply because they received better care in the clinics. The boost of cells, fluids, proteins and electrolytes that come along with blood transfusions may also have helped.

In spite of it all, the World Health Organization is behind blood transfusions and transfer of plasma from ebola survivors. Plasma is the liquid part of blood that contains proteins like antibodies, along with other things like electrolytes and hormones. The first of the eight original transfusion patients, a 27 year-old nurse, was originally supposed to receive plasma and not whole blood. This was because, in 1978, a researcher who received plasma survived an ebola infection brought on by a finger prick in the lab. The nurses’ doctors settled for blood because they didn’t have the right tools to separate the plasma (a process called plasmapheresis).

The seven transfusion patients who followed the nurse ranged from a 54 year-old woman to a 12 year-old girl who caught the virus by kissing her newborn niece just days before the infant died. Antibodies seem to be the most likely explanation for the high rate of survival, but it is still not clear whether they were. Well-controlled human trials to determine whether blood transfusions work for ebola will probably never be possible. But, more and more people may be receiving them, so there may soon be more information about whether and how they work.